by Richard Wagner (1813-1883), music drama in three acts, libretto by Richard Wagner; premiered 26 June 1870 at the Munich Hofoper

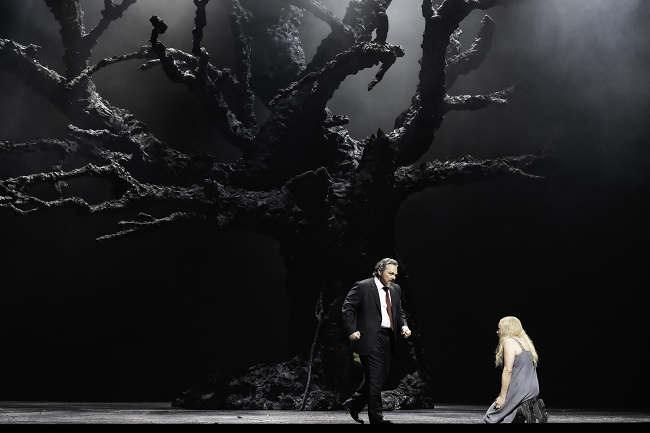

Director: Barrie Kosky, Set designer: Rufus Didwiszus, Costume designer: Victoria Behr

Lighting designer: Alessandro Carletti

Conducter by Antonio Pappano Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

Concert Master: Magnus Johnston

Soloists: Christopher Maltman (Wotan), Elisabet Strid (Brünnhilde), Natalya Romaniw (Sieglinde), Stanislas de Barbeyrac (Siegmund), Marina Prudenskaya (Fricka), Soloman Howard (Hunding), Clare Almond (Erda), and others

Performance attended: 1 May 2025 (premiere)

Summary of the action

Act One

Siegmund, son of Wälse (Wotan), staggers through the forest, seeking shelter from his enemies. He collapses at the hearth of Hunding, unarmed and injured. Sieglinde, wife of Hunding (and daughter of Wälse), discovers him, tends his wounds, gives Siegmund drink, and tells him to rest there until Hunding returns.

Her husband enters and, abjuring the duties of host, questions why Siegmund is in his house. Siegmund divulges his past: the death of his mother, the disappearance of his twin sister, and his recent battle with the brothers of a girl forced – much like Sieglinde, it is revealed – into marriage. The girl was slaughtered and Siegmund’s weapons destroyed, and he explains that he is fleeing her kin. Hunding reveals that he too, through this kinship, is Siegmund’s enemy and declares that they will fight in the morning. Siegmund must in the meantime remain in his house.

Ordered by Hunding to make his drink and await him in bed, Sieglinde returns to Siegmund, disclosing that she has drugged Hunding’s drink. She reveals her past to Siegmund: her loveless, forced marriage and the sudden appearance at the wedding feast of an old man (Wotan), who thrust a sword into the ash tree. The sword, named Nothung, is intended for the hero who will save Sieglinde; neither Hunding nor his guests could move the sword an inch. Siegmund and Sieglinde express their love for one another and Erda appears with spring flowers to bless their union. When Siegmund names his father as Wälse, Sieglinde realises that her twin brother has been found. Siegmund pulls the sword from the tree.

On a dingy side street, Wotan commands the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, his favourite daughter, to protect Siegmund in his forthcoming duel with Hunding. Fricka arrives in a Rolls Royce, chauffeured by Erda, and declares that Hunding has called upon her as protector of marriage and family values. The twins must be punished for their incest and adultery. She argues with Wotan, and forces him to see that Siegmund is not free and thus unable to recover the ring from Fafner and save the gods. Devastated, Wotan agrees not to protect Siegmund in battle and orders Brünnhilde likewise, much to her dismay.

Meanwhile, Sieglinde is running from Siegmund in a panic, convinced that she is unworthy of her brother’s love due to her abusive marriage to Hunding. Siegmund attempts to comfort her, and she falls asleep in exhaustion. Brünnhilde appears and informs Siegmund that he will die in the battle with Hunding. She describes the delights of Valhalla, but, when Brünnhilde maintains that Sieglinde will remain on earth without Siegmund, he refuses to follow Brünnhilde there. He moves to kill Sieglinde, even after Brünnhilde reveals she is pregnant with his child. Brünnhilde intervenes and declares that she will give Siegmund the victory in battle.

The battle commences, as Sieglinde watches on in terror; Brünnhilde assists Siegmund, only for Wotan to appear and shatter Nothung, holding Siegmund still as Hunding stabs the hero to death. Brünnhilde and Sieglinde flee, taking the fragments of the sword. Wotan kills Hunding and sets off in furious pursuit of his disobedient daughter.

Act Three

The Valkyries appear, one by one, from the depths of a tree and, now in a charnel house, pick through the bones and armour of dead heroes. Brünnhilde appears in haste, dragging Sieglinde behind her, and seeks their protection from Wotan. Her sisters refuse to defy their father. Brünnhilde tells Sieglinde that she is pregnant with Siegmund’s child, and Sieglinde becomes frantic to save her unborn son (Siegfried). She flees to the forest as Wotan appears, and the Valkyries try to hide Brünnhilde from his wrath. Brünnhilde is eventually forced to face her father, and he declares that she will become a mortal woman, bound to the man who wakes her from sleep. Wotan forces the other Valkyries to leave.

With much difficulty, Brünnhilde persuades Wotan to encircle her sleeping form with a ring of fire, to protect her from cowards. Only a true hero will be able to reach and wake her. They reconcile and, as Wotan departs, he invokes Loge, and the tree in which Brünnhilde now sleeps is set alight.

Performance

Bleak and grey is the prospect for this production of Die Walküre, to reflect the degradation of human and divine characters alike. A number of the directorial choices are questionable – foremost among them being the Act Two arrival of Fricka in a Rolls Royce, inexplicably wielding Wotan’s spear, and an incongruous, recitative-like episode later in the Act in which Brünnhilde addresses the audience in front of the blackout cloth (clearly to facilitate a difficult scene change). The production’s effective use of colour, however, is beyond dispute. In Act One, the vibrancy of the spring flowers, plucked from Erda’s basket, are in sharp contrast to the blackened tree bark effect of the set. The floral display symbolises Siegmund and Sieglinde’s love, bringing joy into both their woeful lives, yet also, in its incongruous vibrancy, gestures to their passionate delirium, for a time precariously distracted from the realities of the world in which they live and fantasising about their escape from such misery. The effective use of lighting in Act One shows the audience that this will not be possible – shadows on the backdrop crowd in on the lovers from all sides, while the call of Hunding’s hunting horn regularly rings out across the auditorium.

In Act Two, Wotan is no more able to escape his reality, from the web of contracts, ties, and treaties that he himself has helped to weave. Kosky places Wotan in a similarly dismal, human sphere – under the dull lights of street lamps, the god’s grandeur and dignity much depreciated. His physically aggressive treatment of Brünnhilde, as she loyally refuses to abandon Siegmund in the impending battle, distances the audience from the god and renders Wotan, crawling across the ground and clinging to his spear for support, a humiliated and almost contemptible figure.

Act Three sees the Valkyries labour as charnel maidens, clad in dirty, grey rags, the blood of wounded heroes staining their arms. Erda watches on, in the Royal Opera House’s cycle an omnipresent silent form, naked and crippled with age and pain. The Valkyries sort through the dirt to find the bones and armour of fallen heroes, their role as warriors who carry dead heroes to Valhalla degraded, much like Wotan’s majesty. A strong, visual parallel is made in this Act with the Nibelung dwarfs of this cycle’s Das Rheingold, labouring in rags under the power of Alberich’s ring. The correspondence that underlies the Ring narrative between Alberich and Wotan – or ‘light Alberich’ – is here made explicit. In the final scene, the tree that has taken the place of Brünnhilde’s mountain is set alight: a final jet of colour on the set, but one that depicts and presages devastation rather than joy.

Singers and Orchestra

The Orchestra of the Royal Opera House gave the stand-out performance in this production. Expertly directed by Antonio Pappano, the sound was rich, Romantic, lingering, and voluptuous. A shout out, in particular, to the full string sound, which owed as much to the care with which the performers caressed the score as to Wagner’s superb orchestration. Despite the scale of a Wagnerian orchestra, the balance was outstanding and the libretto clearly intelligible above, and in dialogue with, the luscious orchestral sound.

Natalya Romaniw’s Sieglinde was excellent; alternately spirited, troubled, passionate, and desperate, as the narrative and her complex character require. The strength of her voice in the upper register was thrilling, and only matched by that of Marina Prudenskaya’s Fricka, a particularly unpleasant and domineering diva in this production. Sieglinde was ably partnered by Stanislas De Barbeyrac as Siegmund, and Christopher Maltman was a masterful Wotan. Elisabet Strid was Brünnhilde and well supported by her fellow Valkyries, who created an electrifying cacophony in Act Three. Soloman Howard, previously Fafner in the Royal Opera House’s 2023 Das Rheingold, was an inspired choice as the abusive Hunding, and his interaction with Romaniw in Act One was agonising to watch.

Conclusion

The premiere of the Royal Opera House’s Die Walküre was a compulsive and harrowing watch. The production drilled down to the debasement and mortification at the core of the narrative, which was only alleviated by the lush, full-bodied orchestral sound. This mesmeric production was, rightly, met with fervent audience applause.

Rebecca Severy MPhil BA (Hons)

PhD Candidate in Music, University of Cambridge

Photograph: Monika Rittershaus

The photo shows: Christopher Maltman was a masterful Wotan, Elisabet Strid was Brünnhilde